An overview of mentorship and mentorship models

Please note that although the material in this module may be presented in a linear manner, mentorship is an ongoing, reflective, and cyclical process.

Mentorship can take many different forms, and now more than ever, boundaries between who is a mentor and who is a mentee are changing. Traditional definitions of mentors as senior leaders who take novice mentees under their wing no longer necessarily apply. Effective mentoring relationships that are built on trust, respect and reciprocity create space for both mentors and mentees to explore and learn more about themselves and their work, and reach goals.

Before starting a mentoring relationship, it is important to reflect on your needs and explore the different ways in which you can and want to become involved in mentoring relationships. In the next few sections, we’ll explore how to define mentoring relationships and what makes them effective.

Learning activity: What does mentorship look to you?

Learning activity: What does mentorship look to you?

Instruction: Explore personal assumptions about mentorship.

Go to your Workbook to jot down what mentorship looks like to you, then click on the checkbox.

Who is a mentor? Who is a mentee?

Sources of mentorship in graduate school can be multifaceted:

- Peer mentorship (mentorship from mentor around the same point on a learning journey)

- Near-peer mentorship (mentorship from a mentor ahead of you on a learning journey – Senior graduate student/postdoctoral fellow)

- Informal mentor (mentorship from individuals who do not have a specific connection to your particular program/project)

- Formal mentor (mentorship from your supervisor(s), committee members)

Source: Lunsford, L. G., Crisp, G., Dolan, E. L., & Wuetherick, B. (2017). Mentoring in higher education. In D. A. Clutterbuck, F. K. Kochan, L. Lunsford, N. Dominguez & J. Haddock-Millar (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring (pp. 316-334). Sage

Research has demonstrated that effective mentorship can improve:

- Graduate students’ academic socialization and support (Hadjioannou et al., 2007);

- Satisfaction with the program and/or advisor (McAllister et al., 2009); and

- Graduate students’ research and writing productivity (e.g., Lunsford, 2012; Watson et al., 2009)

Sources:

- Hadjioannou, X., Shelton, N. R., Fu, D., & Dhanarattigannon, J. (2007). The road to a doctoral degree: Co-travelers through a perilous passage. College Student Journal, 41(1), 160-177.

- McAllister, C. A., Harold, R. D., Ahmedani, B. K., & Cramer, E. P. (2009). Targeted mentoring: Evaluation of a program. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(1), 89-104.

- Lunsford, L. (2012). Doctoral advising or mentoring? Effects on student outcomes. Mentoring & tutoring: Partnership in learning, 20(2), 251-270.

- Watson, J. C., Clement, D., Blom, L. C., & Grindley, E. (2009). Mentoring: Processes and perceptions of sport and exercise psychology graduate students. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(2), 231-246.

Mentorship models

Various mentorship models have been developed to support an awareness or understanding of mentorship within the context of higher education ( Lunsford, L. G., Crisp, G., Dolan, E. L., & Wuetherick, B. (2017). Mentoring in higher education. In D. A. Clutterbuck, F. K. Kochan, L. Lunsford, N. Dominguez & J. Haddock-Millar (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring (pp. 316-334). Sage.Lunsford et al., 2017). Each model differs due to factors like mentor and mentee needs, contexts, time commitment, and type of mentoring relationship (e.g., formal, casual, temporary).

The models described in this module are not meant to be prescriptive. They should instead be used as tools to create and sustain mentoring relationships that will best meet your needs and goals. You may find that you will use different approaches or models with different people, and that the approaches or models change over time. Committing to clear and open communication in the mentoring relationship will help with selecting the approaches that best align with your needs, and with deciding if and when changes to the approach are needed as the relationship evolves.

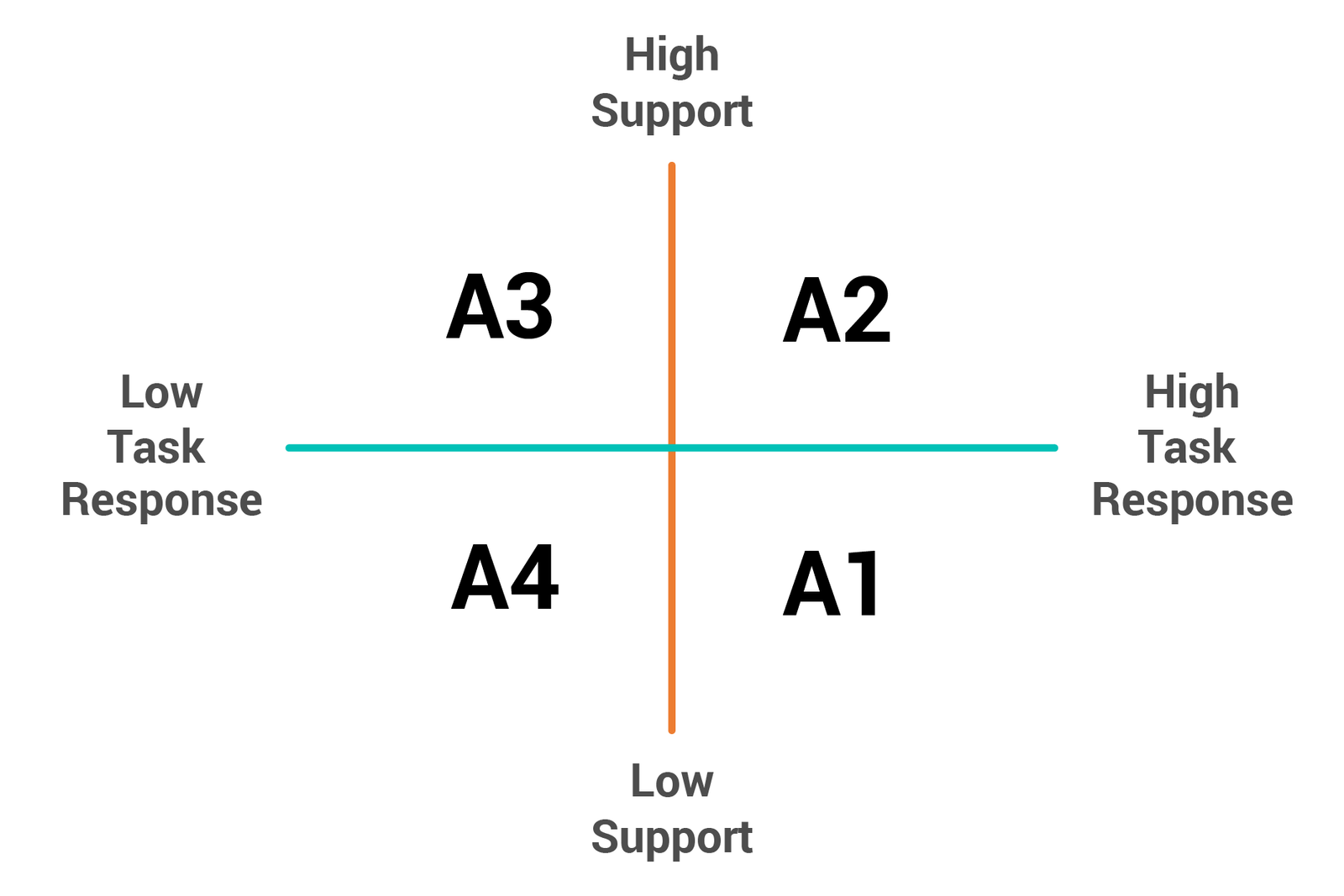

Adaptive mentorship

Developed by Canadian scholars Keith Walker and Edwin Ralph, adaptive mentorship is a model of mentorship focused on ensuring that mentors understand and adapt their mentorship behaviours in response to the task-specific developmental needs of their mentees ( Ralph, E., & Walker, K. (2013). The promise of adaptive mentorship: What is the evidence? International Journal of Higher Education, 2(2), 76-85.). They argue that the mentorship behaviours are influenced by the psychological, social, organizational, and cultural aspects of the mentorship setting.

Adaptive mentorship relies on three phases of mentoring relationships.

Indigenous mentorship

A second model for understanding mentorship was recently developed by Canadian scholars Murry et al. (2021) who worked with Indigenous graduate students in the health sciences to understand their needs from a mentor.

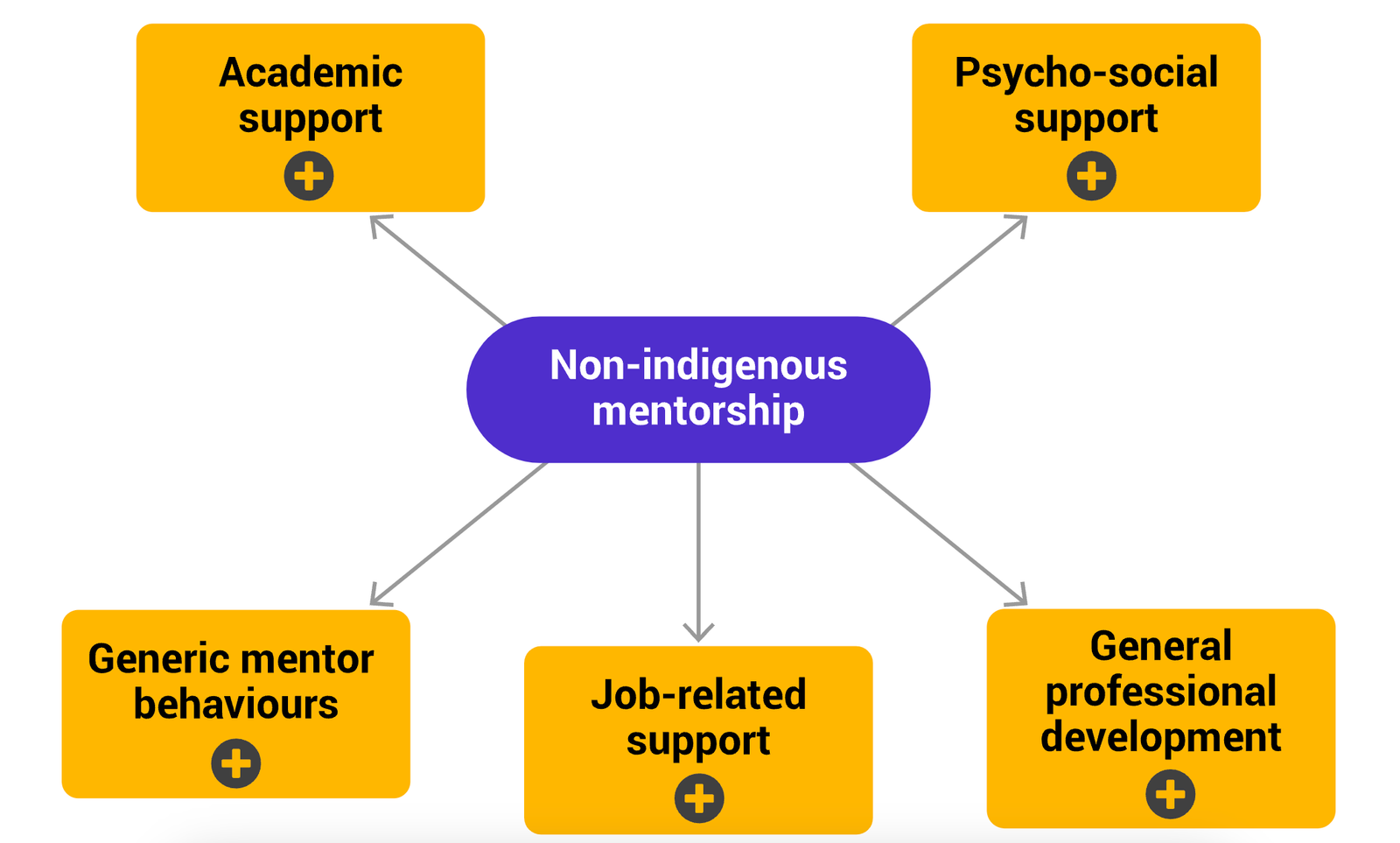

In their research they found that all mentors needed to provide support in five broad areas:

- Academic support (assistance navigating the academic program or courses, or navigating the broader graduate student experience)

- Psycho-social support (affirming professional and personal identity, cultural competence and awareness, empathy, and empowerment)

- Job-related support (career counselling or experiences, support for curriculum vitae development or preparing dossier for awards or jobs)

- Core (or generic) mentor behaviours (setting expectations, providing constructive feedback, modeling critical behaviours)

- General professional development (exposing mentee to networks, developing specific research skills or professional skills)

Instruction: Explore the components of a non-Indigenous mentorship model where the mentee is not Indigenous by reviewing the sections below.

Academic support

- Assistance navigating academic program

- Offering advice for coursework success

- Providing opportunities for graduate school-related practices

Psycho-social support

- Affirming mentee’s professional identity

- Affirming mentee’s value as a person

- Empowering the mentee to take initiative

- Providing advice on work-life balance

- Offering psychological support

- Providing counseling during hardship

- Developing a friendship with the mentee

- Demonstrating commitment to mentee despite conflicts

- Creating an inclusive environment

- Addressing stereotype threat in mentee performance

- Exhibiting cultural awareness

- Practicing cultural competence

Generic mentor behaviors

- Setting expectations

- Engagement with student

- Constructive feedback

- Role modeling critical behavior

- Facilitating learning

Job-related support

- Discussing job-related processes (e.g., tenure expectations)

- Reviewing mentee resume/CV

- Offering job/career consulting

- Discussing job specific skills

- Providing opportunities for career exploration

General professional development

- Exposing mentee to networks

- Providing research assistance

- Providing advice on professionalism skills

- Providing opportunities for work-related practice

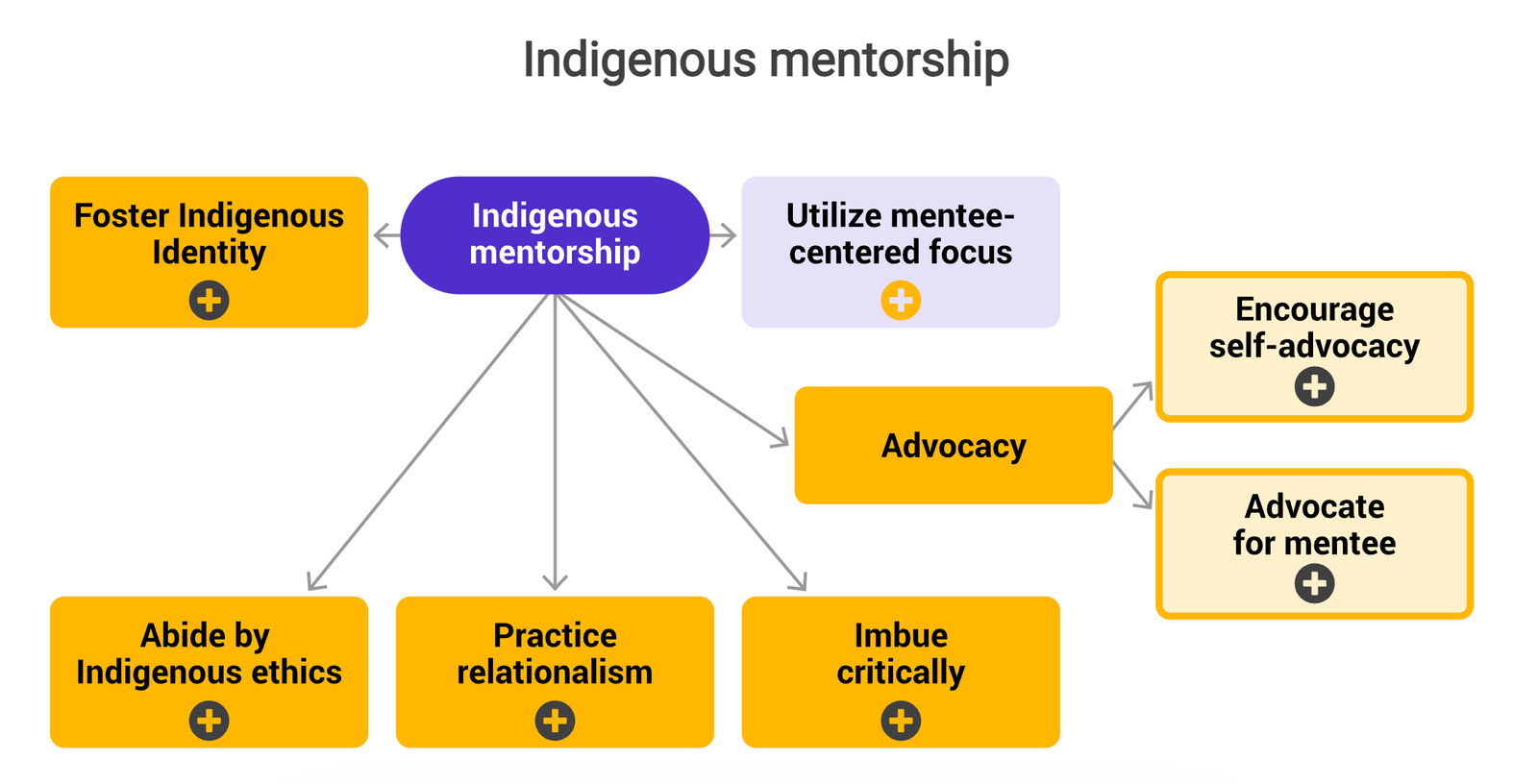

They also found that Indigenous graduate students required a different dimension of support, specific to the experiences and contexts of those Indigenous students. In particular they identified six additional areas that may be required for Indigenous mentees:

- Fostering Indigenous identity (understanding identity continuum, connecting students to Indigenous community);

- Abiding by Indigenous ethics (following traditional Indigenous protocols and etiquette);

- Practicing relationalism (reciprocity, trust, and personal connection);

- Imbuing criticality (decolonizing theory and practice, develop resiliency, create space for critical discussions);

- Using a mentee-centered focus (considering the student’s holistic development, focusing on wellbeing, supporting different definitions of success); and

- Focusing on advocacy (encouraging skills for self-advocacy, and proactively advocating for mentee with individuals and within systems).

Instruction: Review the following image and explore the components of an Indigenous mentorship model for Indigenous mentees by clicking on each section below.

Utilize mentee-centered focus

- Tailor mentorship to student’s needs

- Consider holistic development

- Share responsibilities

- Support different definitions of success

- Commit to student’s well-being over own

Encourage self-advocacy

- Prepare mentee for outside world

- Empower mentee sense of self

- Encourage mentee to find allies

Advocate for mentee

- Teach colleagues about racism

- Work with colleagues to address unique student difficulties

- Change the system for future mentees (e.g., including Elders on dissertation committee)

Imbue criticality

- Decolonize theory

- Develop resiliency

- Create spaces for critical discussions

- Bridge crisis of relevance

- Buffer institutionalized mindset

Abide by Indigenous ethics

- Follow traditional Indigenous protocols

- Follow traditional Indigenous etiquette

Practice relationism

- Practice reciprocity

- Practice egalitarianism

- Establish trust

- Prioritize the personal over professional

Foster Indigenous identity

- Understand Indigenous identity continuum

- Connect students to Indigenous community

- Affirm Indigenous identity

- Situate one’s own Indigenous identity